Rubin Observatory will detect thousands of brown dwarfs, unlocking Milky Way mysteries

Vera C. Rubin Observatory will capture the faint light of distant brown dwarfs to help scientists understand the Milky Way’s formation and evolution.

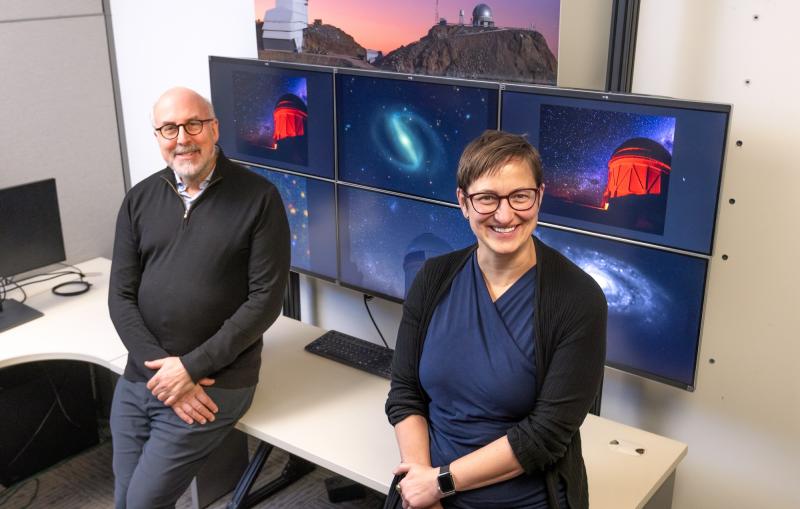

LSST Camera

Vera C. Rubin Observatory will search wide and deep into the cosmos for signs of dark matter and dark energy and yield new insights into our own galaxy and solar system. SLAC built Rubin's LSST Camera (above), the largest camera ever built for astrophysics. SLAC will also host Rubin's U.S. Data Facility and co-lead the observatory's operations along with NSF's NOIRLab. (Image Credit: Jacqueline Ramseyer Orrell/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory)

One could argue that brown dwarfs don’t get the love they deserve. Sometimes referred to as “failed stars,” they don’t have enough mass to sustain nuclear fusion, which powers all stars, including our sun. But they are also too big to be considered planets, with some having 75 times the mass of Jupiter. Despite not fitting neatly into one of these familiar categories of astronomical objects, brown dwarfs hold important clues to the processes that formed the Milky Way. NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory, jointly funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) and the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science (DOE/SC), will soon reveal a never-before-seen population of brown dwarfs beyond the sun’s local neighborhood, giving scientists more tools to map the history and evolution of our home galaxy.

“Brown dwarfs are these weird, intermediate objects that defy classification,” said Aaron Meisner, associate astronomer at NSF NOIRLab and a member of Rubin Observatory’s Community Science Team. In addition to being smaller than stars, brown dwarfs are much cooler, with surface temperatures ranging from about 0 to 2,000 degrees Celsius (32 to 3,600 degrees Fahrenheit). That means they don't produce very much light in the visible spectrum, which makes them difficult to detect with optical telescopes. “It’s possible we’re swimming in a whole sea of these objects that are really faint and hard to see,” said Meisner.

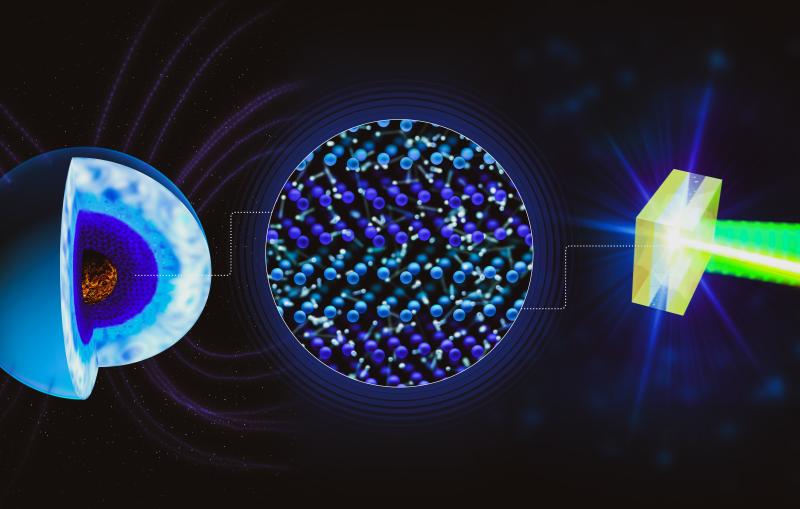

The same qualities that make brown dwarfs unusual and elusive also make them excellent candidates for helping scientists disentangle the Milky Way galaxy’s formation and evolution, which was strongly influenced by mergers with smaller, nearby galaxies. Brown dwarfs have longer life spans than the larger, hotter stars, so distant brown dwarfs that formed in the early universe are still out there, largely unchanged and containing valuable information about the Milky Way early in its history. By studying the properties of these ancient brown dwarfs, scientists can trace them to their original galaxies and reveal any changes in how Milky Way stars formed over cosmic time.

For ten years, beginning in late 2025, Rubin’s Simonyi Survey Telescope will scan the sky from its vantage point on Cerro Pachón in Chile. Rubin will take wide, detailed images using the LSST Camera – the largest digital camera in the world – and covering the entire visible sky every few nights. Rubin’s six camera filters will transmit light from a broad range of optical wavelengths, and into the near-infrared. Rubin’s near-infrared capability, combined with its wide field of view and ability to see deep into space, will make it a powerful detector of faint objects that emit mainly infrared light, like brown dwarfs. Detailed predictions of the distant brown dwarfs Rubin will see have recently been performed by Christian Aganze, a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University.

Rubin will capture the light from brown dwarfs at far greater distances than previous visible light surveys. Existing optical surveys like Pan-STARRS and Sloan Digital Sky Survey have mainly helped us discover brown dwarfs that are relatively close by. “Current surveys go to a distance of about 150 light-years from the sun for ancient brown dwarfs in the Milky Way’s halo,” said Meisner. “But Rubin will be able to see more than three times farther than that.” This increase in distance means an even bigger increase in the total volume of space available for scientists to find and study these brown dwarfs – offering scientists the larger sample of these faint objects they’ve ever had.

Researchers like Meisner are excited at the prospect of finding enough distant brown dwarfs to study on a population level instead of individually, so they can compare the properties of different subgroups and look for patterns in the way they’re distributed.

“Rubin will reveal a population of ancient brown dwarfs about 20 times bigger than what we’ve seen up to now,” said Meisner. “That will allow us to decipher which pieces of galactic substructure different brown dwarfs came from, and lead to major advances in our understanding of how the Milky Way’s populations formed.”

Rubin Observatory is a joint initiative of the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the Department of Energy (DOE). Rubin is operated jointly by NSF’s NOIRLab and SLAC.

This article is based on a story from the Rubin Observatory.

For questions or comments, contact SLAC Strategic Communications & External Affairs at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.